As Instagram tests hiding likes, China’s social media services fight a similar battle

Weibo, Alibaba's Youku, and Baidu's iQiyi are among the Chinese social media platforms trying to rein in an online popularity contest

It’s possible that one day no one will know how many people have liked your Instagram posts.

Starting this week, Instagram will start hiding likes for some users in the US, following similar tests in Australia, Brazil, Canada, Ireland, Japan and New Zealand. CEO Adam Mosseri said the idea is to “depressurize Instagram, making it less of a competition.”

The story of China’s Great Firewall, the world’s most sophisticated censorship system

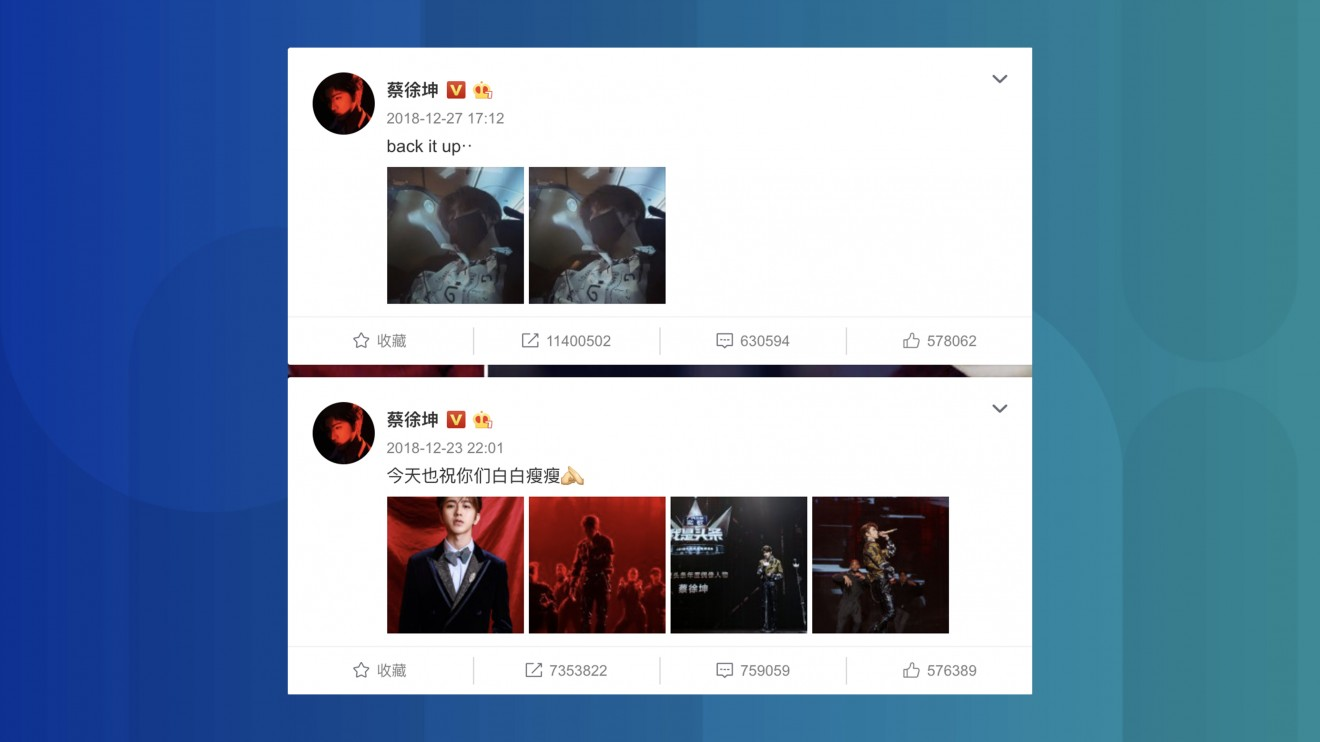

Without access to Instagram or Twitter, China’s public social chatter largely occurs on Weibo. That’s where “water loading” -- the practice of using droves of real or fake accounts to inflate social traffic -- has come under particular scrutiny.

How Weibo became China’s most popular blogging platform

Accusations of "water loading" also extend outside China’s firewall.

How Youku went from being China’s YouTube to China’s Hulu

(Abacus is a unit of the South China Morning Post, which is owned by Alibaba.)

But all these efforts haven’t stopped people -- especially ardent fans -- from trying to game the system.

For these dedicated fans, it’s about trying to keep their favorite stars ahead of the competition. As one person said, “Fans of other stars are inflating [traffic], how can we not?”

Some users and analysts say as long as some sort of popularity metrics exist, it’s difficult to stop people from trying to manipulate them.

For more insights into China tech, sign up for our tech newsletters, subscribe to our award-winning Inside China Tech podcast, and download the comprehensive 2019 China Internet Report. Also roam China Tech City, an award-winning interactive digital map at our sister site Abacus.