Doxxing has become a powerful weapon in the Hong Kong protests

Having your private information leaked for political reasons may become the new normal

“Since my personal information has been posted online, I get a lot of hidden phone calls,” said David, a victim of Hong Kong’s recent doxxing boom.

David, an alias used to avoid bringing further unwanted attention, had his private information leaked on a website that targets Hong Kong protesters and anyone thought to support them.

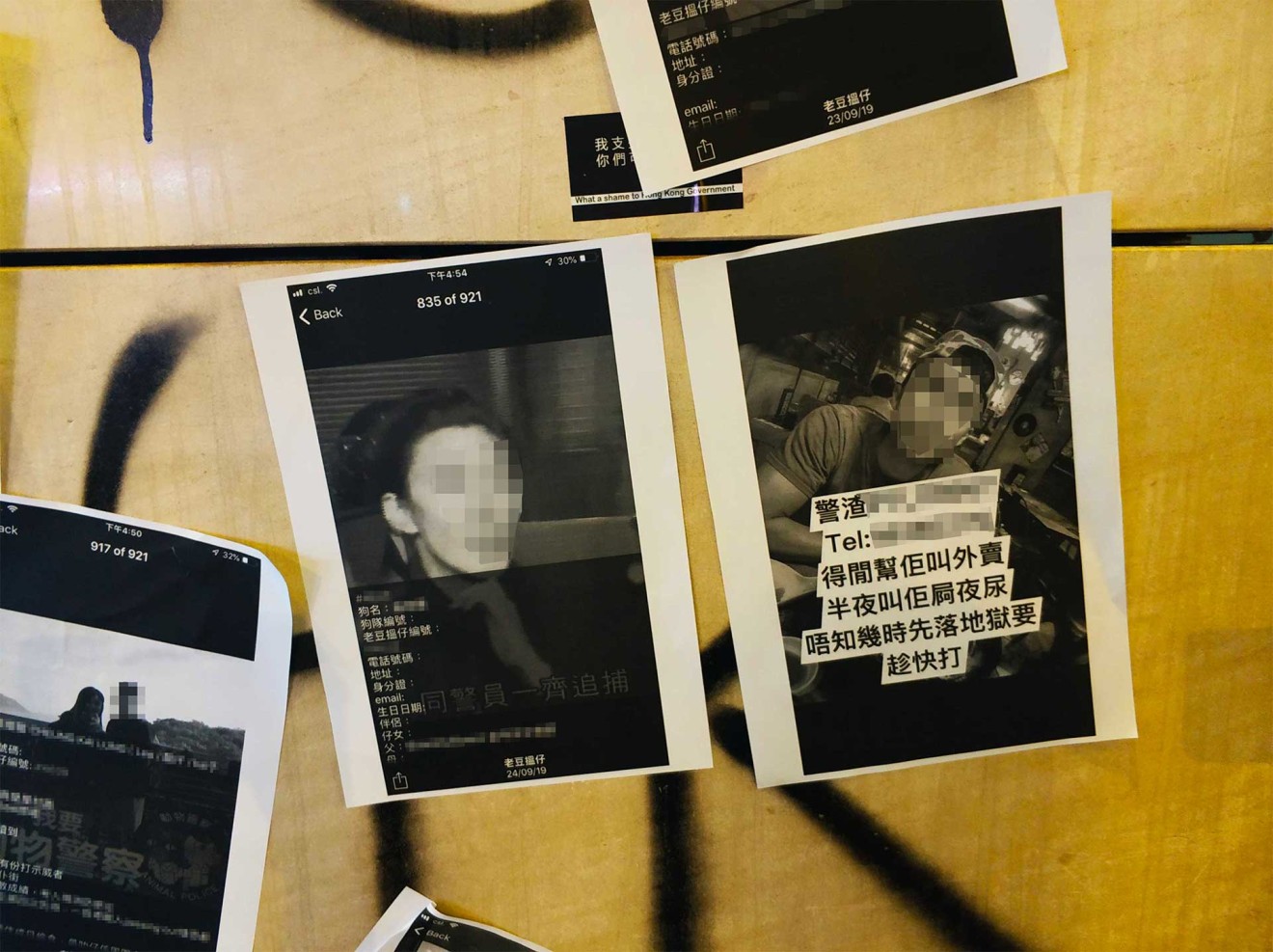

And he’s not alone. Hundreds of people on both sides of the conflict in Hong Kong have had their sensitive personal data posted online, from protesters to police, activists to government officials.

In David’s case, alongside his own date of birth, phone number and address, the site also shows the name of his parents and their addresses.

“They don't know about that,” said David, who is in his mid-twenties.

David’s information was posted to a site called HKleaks, which targets activists, journalists, social workers and even local media magnates. The top banner of the site makes its intent clear:

“There's no escaping for any of them. We need to make all the rioters feel like they have nowhere to hide.”

Doxxing, the leaking of personal information for harassment and malicious intent, has long been a favored tool for keyboard warriors. Now it’s becoming an ever more prominent part of the anti-government protests in Hong Kong, which have gone on for months.

“This is something totally new,” said Kanishk Karan, a research associate at DFRLab, Atlantic Council, which published a report on doxxing on the messaging app Telegram.

Mr. Ng, a police officer, said that doxxing started after he appeared on TV and someone shared his Facebook profile in the comment section of a local news outlet. Accompanying it were pictures of his wife and child.

“My daughter is three years old now, turning four next month,” said Ng, adding that a picture of her with all her classmates at a sports game was posted online.

A month later, his detailed information appeared in a Telegram group called “Dads searching for sons,” including his name, ID, phone number and photos. He started receiving anonymous calls, and when he blocked those numbers, calls started coming from restaurants asking about reservations that he never made. His wife also suspected her Facebook account might have been affected when she found she could no longer log in.

After the doxxing, Ng decided to keep his Facebook account and phone number -- he said he’s not afraid. But the leak of his family’s information was worrying.

“I’m worried that they might run into people who might be more extreme -- not sure what would happen,” he said.

“It's used because it works; victims are often intimidated,” he said.

In Hong Kong, doxxing is becoming a potent weapon. And as social movements increasingly depend on the internet to organize and formulate demands, as with the current protests, we may see more of it.

“It's becoming more like a political vendetta,” Karan said. “This might be something that we will see more often as social protests keep going on.”

The wave of protest-related doxxing started in June along with the anti-extradition movement -- the first mass rallies were organized to oppose a law that would allow extradition to China. Between June 14 and September 19, the Office of the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data has received almost 1,400 complaints of doxxing and cyberbullying.

To put that into perspective, the office only had 29 doxxing cases through June 13. Among the doxxed, 41% are police officers, said the Privacy Commissioner Stephen Wong.

“Both camps, pro-government people and pro-protest people, believe that doxxing is a way to punish wrongdoers for their misdeeds and to deter the other side from any further action,” said Michael Cheung, assistant research officer at the University of Hong Kong’s Law and Technology Centre.

By now, many names have been leaked online from both sides of the conflict. In many cases, mere speculation is enough to get a person doxxed. David, for instance, told us that the doxxing website falsely accused him of being a rioter.

However, according to Karan’s research, pro-democracy demonstrators face greater danger when their information is leaked.

How to protect your smartphone data if border agents ask for your phone

In order to stem the tide of doxxing, the Office of the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data said that it has set up a special team, handed over cases to the police and contacted platforms to remove personal information. Cheung, however, believes that protest-related doxxing is happening because the existing laws and its enforcement may be inadequate.

Meanwhile, for those seeking to protect their data online, checking your social media for any personal information is a good start, said Karan.

For more insights into China tech, sign up for our tech newsletters, subscribe to our Inside China Tech podcast, and download the comprehensive 2019 China Internet Report. Also roam China Tech City, an award-winning interactive digital map at our sister site Abacus.